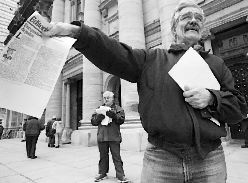

CHERYL HNATIUK, GAZETTE / Duplessis orphans Louis-Joseph Hebert (front) and Gabriel Boyer hand out leaflets yesterday at Mary Queen of the World Cathedral.

Copied from The Montreal Gazette

CHERYL HNATIUK, GAZETTE / Duplessis orphans Louis-Joseph Hebert (front) and Gabriel Boyer hand out leaflets yesterday at Mary Queen of the World Cathedral. |

As Cardinal Jean-Claude Turcotte said Good Friday mass at Mary Queen of the World Cathedral yesterday, about a dozen Duplessis orphans stood outside in the biting wind to demand an apology for years of abuse at the hands of the church.

They parked a rented billboard sign on the sidewalk outside the magnificent cathedral that read: Monseigneur Turcotte. Alive and Still Waiting. The Duplessis Orphans. Happy Easter.

"Good Friday is a dark day in the church," said Rejean Hinse, one of the orphans. "But we live Good Friday 365 days a year."

The orphans suffered years of abuse in Catholic Church-run homes, institutions and psychiatric hospitals during the 1940s and '50s when Maurice Duplessis was premier of Quebec.

They say many lives were ruined because of the abuse.

"Thousands have suffered because of the tragic events of the past," Hinse said. "Children were locked in isolation cells for years at a time, they were used as guinea pigs for medical tests - they had their childhoods ripped from them."

For years, the orphans have been demanding an official apology from the church and the Quebec government, financial reparations and a public inquiry.

Yesterday, they used the holy day of atonement to call attention to the church's refusal to acknowledge their suffering.

"We've written so many letters and (Turcotte) won't even sit at the same table as us," Hinse said. "There's been no recognition."

About 1,000 Duplessis orphans are still alive today, but many live in poverty and suffer from psychological problems. There is also a high suicide rate among the group.

Clairina Duguay and her sister, Simonne, were taken from their family at age 9 and 7 after their mother died.

They were sent to a psychiatric hospital, but their family believed they were in an orphanage in the care of nuns.

Her husband showed a black binder brimming with documentation they have collected about those dark years, like medical charts that show she was tested unnecessarily for syphilis and another file that states falsely all her siblings were "retarded."

"I want justice and then damages," said Duguay, who will be the subject of a documentary on the orphans by Hollywood director William Gazecki.

Gilles Bourbonniere, 59, was bounced from institution to institution from age 5 until he turned 18.

He experienced "too many things," he said, but what really bothered him was that no one ever bothered to offer him schooling.

"I'm learning now, though. I've been going for a few years," he said.

"But I want the government to finally recognize what happened to us. We've been waiting and waiting."